Welcome to Jurassic Park

An adventure 65 million years in the making.

In 1992 and into 1993, I would have been deep into my childhood dinosaur obsession. We were doing a dinosaur unit in Mrs. McPartlands's second grade classroom, where I was the resident expert. At home, I kept a shoebox with all my dinosaur treasures: a dinosaur coloring and activity book, plastic toys, a mechanical "Dino Pet" keychain, and other precious items. But worldwide dinomania was yet to begin.

I have a very distinct memory from the spring of 1993, when my mother showed me small inset story in a magazine she was reading, and noted, "They're making a movie where they bring dinosaurs back to life."

You can check out footage of me at nine years old watching Jurassic Park in the theater for the first time in July 1993 here.

Press

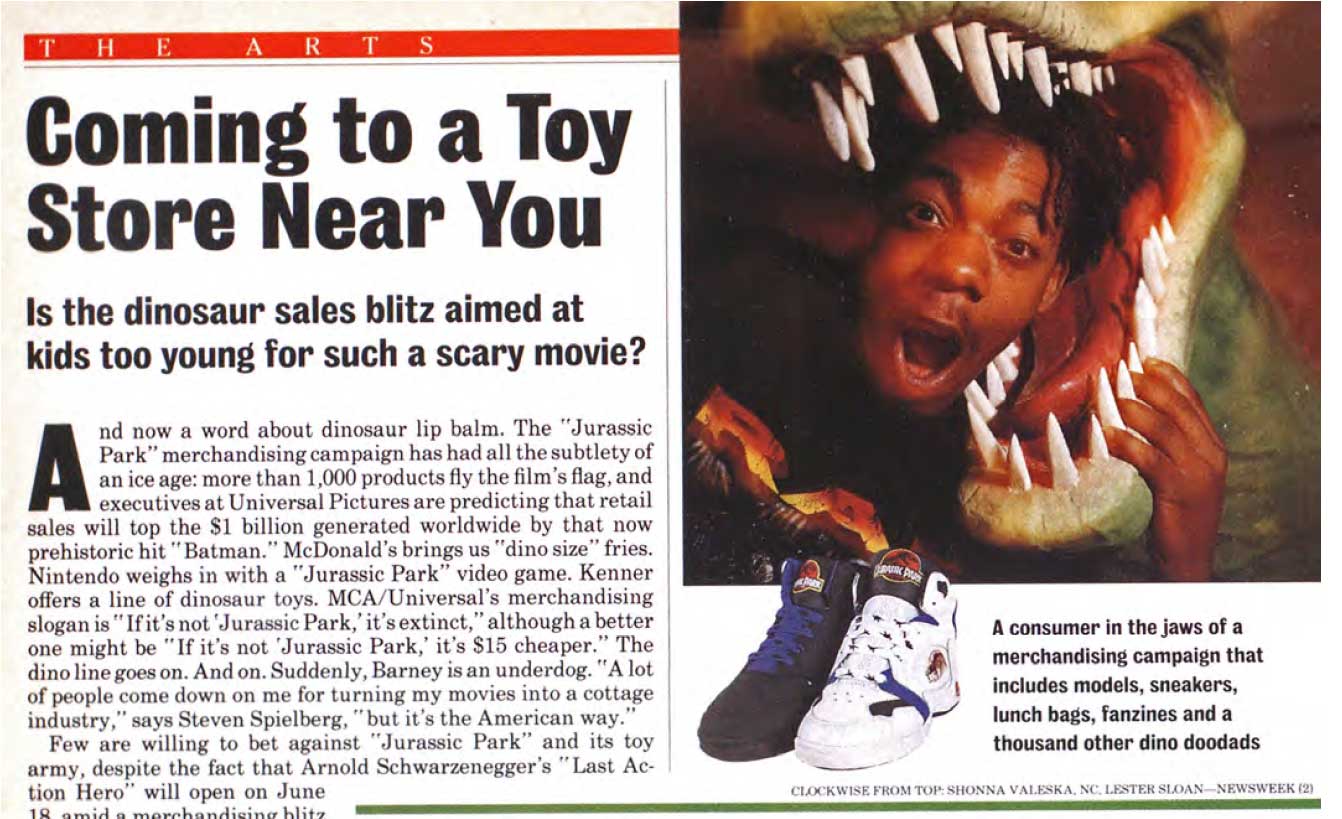

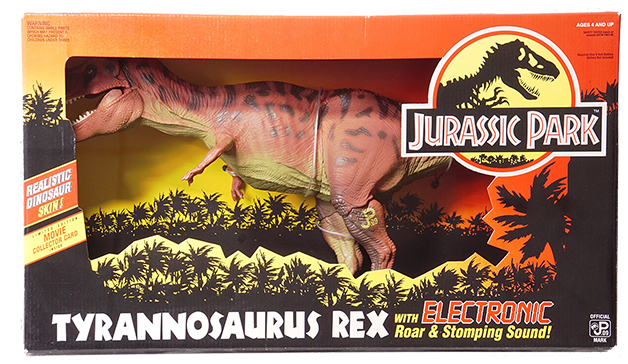

Jurassic Park was marketed heavily to children, but this was somewhat controversial at the time, since the movie was considered too scary for younger children, as discussed in this article from Newsweek (printed alongside the film review). The movie was rated PG-13, which would usually be considered too diecy for Happy Meal promotions, yet kids still enjoyed dinosaur toys and collectable Jurassic Park cups alongside their chicken nuggest and fries in the summer of 1993.

In his August 1993 essay for The New York Review of Books, Stephen Jay Gould, the American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science, coined the term "dinomania."

The Science Teacher is a peer-reviewed professional journal for secondary and high school science teachers published by the National Science Teachers Association. This article from the November 1993 issue, shares ideas for using interest in Jurassic Park to encourage science learning and exploration around topics such as ecosystems, extinction theories, climate and weather patterns, genetic engineering and more.

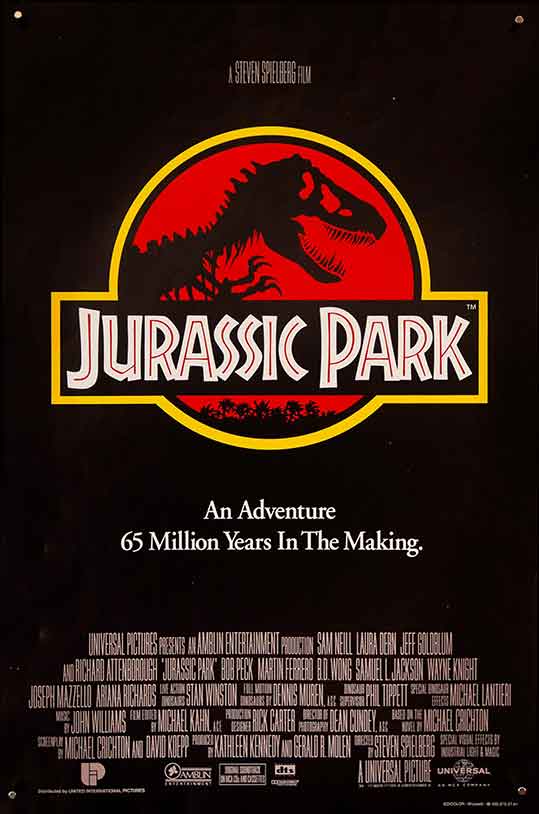

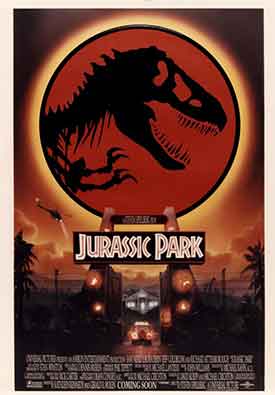

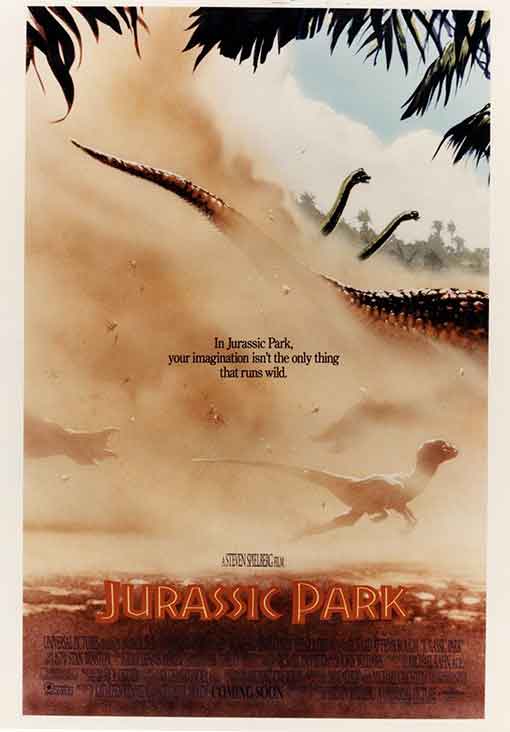

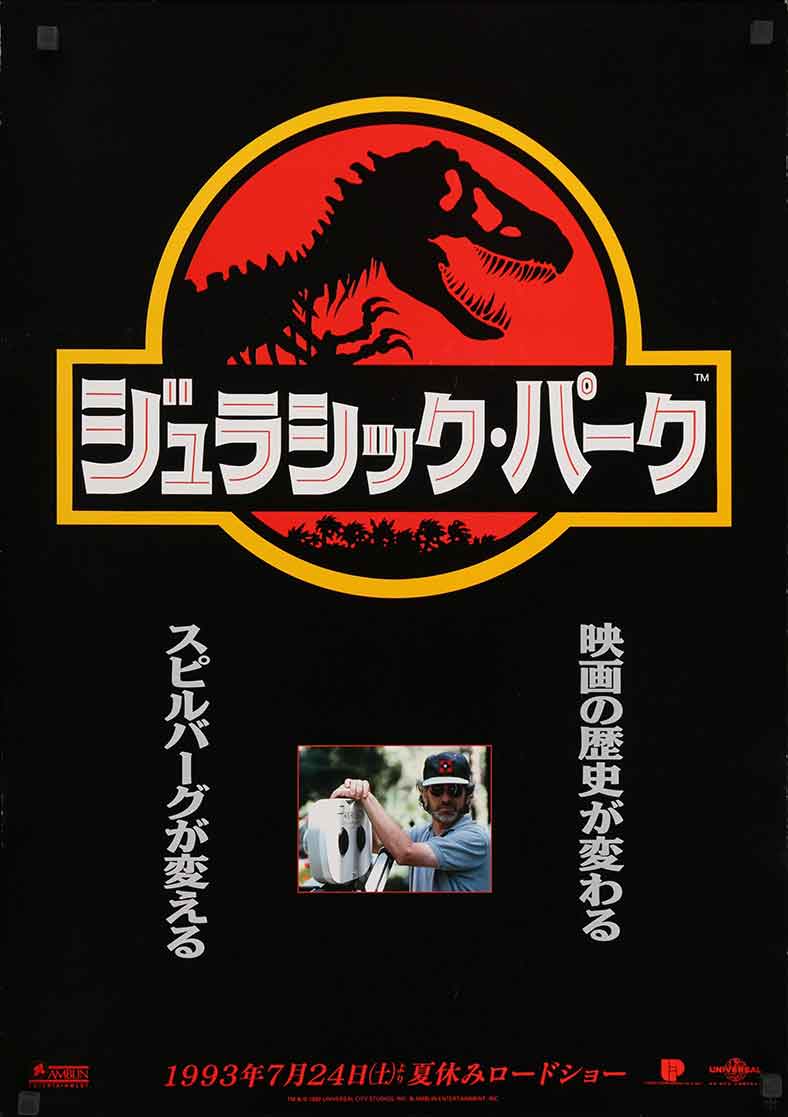

Posters

Toys

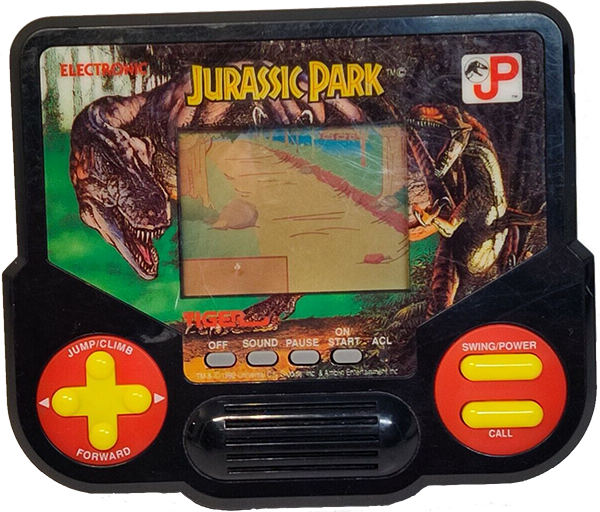

Video Games

Bibliography

- Baird, R. (1998). Animalizing Jurassic Park’s Dinosaurs: Blockbuster Schemata and Cross-Cultural Cognition in the Threat Scene. Cinema Journal, 37(4), 82–103.

- Bullock, P. (2020). Jurassic Park. Auteur.

- Clark, B. L., & Higonnet, M. R. (Eds.). (1999). Imagining Dinosaurs. In Girls, boys, books, toys: gender in children’s literature and culture (pp. 183–195). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Giles, J. (1993, June 14). Coming to a toy store near you. Newsweek, 121(24), 64–65.

- Gould, S. J. (1993, August 12). Dinomania. The New York Review of Books, 40(15).

- Hitt, J. (2001, October 1). Dinosaur Dreams: Reading the Bones of America’s Psychic Mascot. Harper’s, 33–41.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (1998). The last dinosaur book: the life and times of a cultural icon. University of Chicago Press.

- O’Neill, J. (1996). Dinosaurs-R-Us: The (Un)Natural History of Jurassic Park. In J. J. Cohen (Ed.), Monster theory: Reading culture (pp. 292–308). University of Minnesota Press.

- Shay, D., & Duncan, J. (1993). The making of Jurassic Park (1st ed). Ballantine Books.

- Simmons, P. E., & Wylie, C. (1993). Exploring Jurassic Park. The Science Teacher, 60(8), 50-53.

- Wollen, P., & Sheehan, H. (1996). Theme parks and variations. Sight and Sound, 3(7), 6–10.